ASM Cobalt’s role and the green energy transition: championing equitable supply

As we launch into 2022, we’re also reflecting on the progress we made at the Fair Cobalt Alliance in 2021. Last year, we welcomed new members from across the battery supply chain and stepped up our operations to improve mine sites, support child labour remediation and much more. Globally, the pressure to act around the supply of cobalt also ramped up, particularly around November as COP26 brought a raft of new targets to address the climate crisis.

One of those targets was an agreement by 32 countries and hundreds of businesses and regions to end the sale of petrol and diesel vehicles by 2040. In 2019, 16% of the European Union’s greenhouse gas emissions came from car and van transport, and in the same year, only 3.5% of cars registered in Europe were electric.

These timeframes and statistics shed a light on the scale of the impact of vehicular transport and the required pace of change. Underpinning this transformation are batteries, and battery metals such as cobalt.

Mare than 50% of the world’s cobalt is found in the DRC, where the Fair Cobalt Alliance operates. This concentration of a highly valuable resource has seen the international spotlight shine on the conditions at informal, artisanal mine sites, reporting widespread child labour and hazardous working conditions.

OECD research into cobalt’s interconnected supply chain shows us that despite efforts, few downstream companies can be certain there is no artisanal-mined (ASM) cobalt in their products. ASM cobalt travels across the world, with the majority then mixed and further processed in China, making it hugely challenging to differentiate the sources of materials subsequently used in the cathodes. When coupled with the unique properties of cobalt for battery performance, this means that disengaging from a vital source of the metal would be hugely counterproductive for meeting global electrification targets.

Source : Cobalt Institute

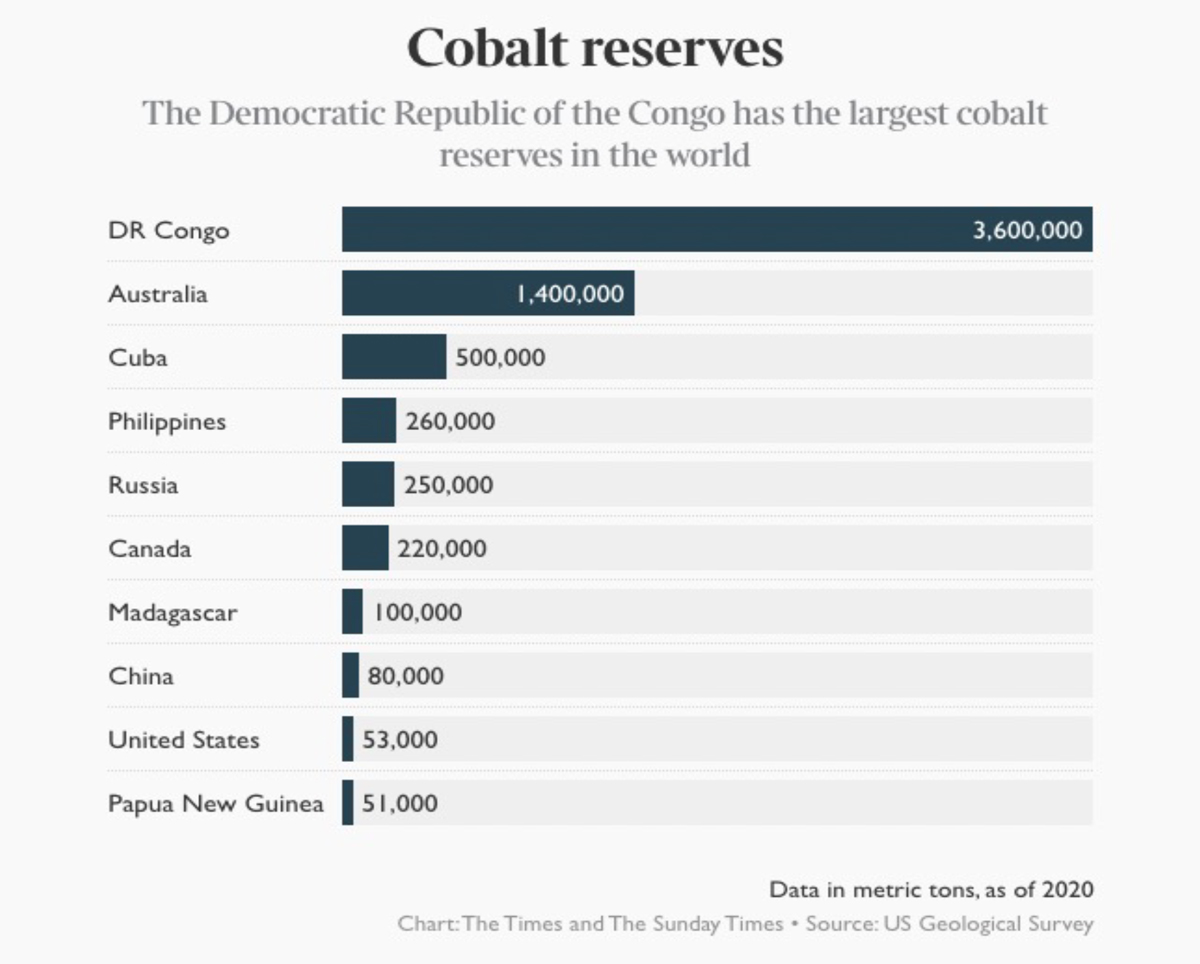

Source: The Times & Sunday Times – US Geological Survey

The DRC’s cobalt reserves far outstrip those found in any other country.

But why do we need all this cobalt?

Cobalt, already widely used in batteries of phones, laptops and tablets, is critical for powering electric vehicles. As part of the battery cathode, cobalt increases energy density and stabilises the battery, allowing for frequent and safe recharging. These same properties make it valuable for storing energy from intermittent sources too – a technology that will become increasingly important as countries transition towards solar and wind energy.

If we are to meet the ambitious targets for the electrification of transport and industry, it is clear that we will need a range of solutions. Cobalt will remain crucial and will continue to dominate the market given these important characteristics. Technologies that reduce the quantity of cobalt required continue to rely on metals that must also be mined, meaning that ESG risks are simply being displaced, rather than resolved.

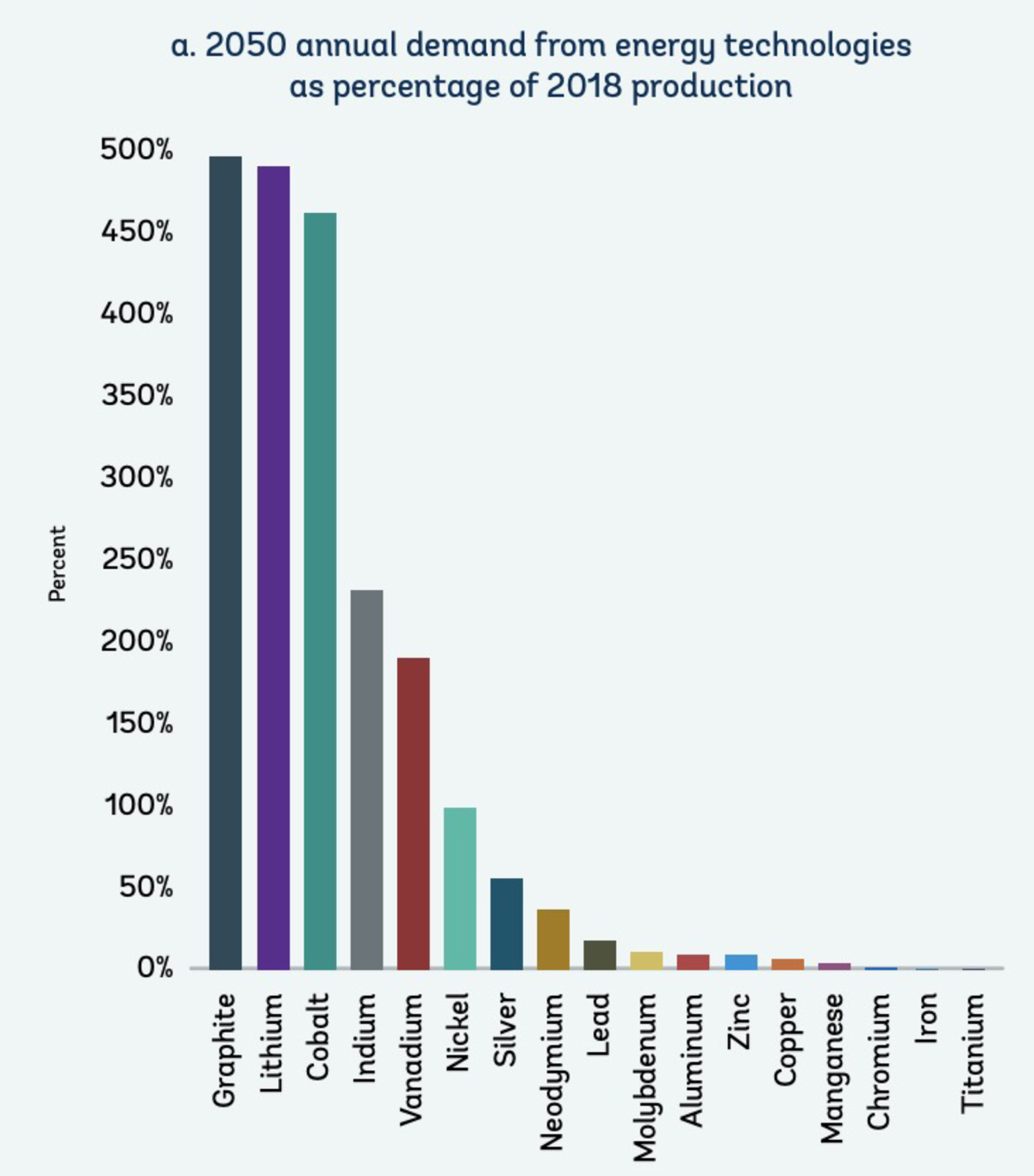

Source: 2020 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ World Bank Report: Minerals for Climate Action: The Mineral Intensity of the Clean Energy Transition.

World Bank predictions under IEA’s 2-degree scenario, showing that production of graphite, lithium and cobalt will need to be increased by more than 450% by 2050 from 2018 base levels to meet anticipated demand.

Therefore, rather than viewing alternatives such as solid-state batteries, lithium iron phosphate or high-nickel cells as a ‘way-out’ from cobalt, they need to be developed in parallel, with different battery chemistries suited to different applications. With cobalt-based batteries currently offering the best range for drivers, alternatives are unlikely to take cobalt’s place in the market.

Perspective shift

Reaching the targets set for EV take-up at COP26 will require cross-sector collaboration at an unprecedented scale; and create coalitions pushing for change.

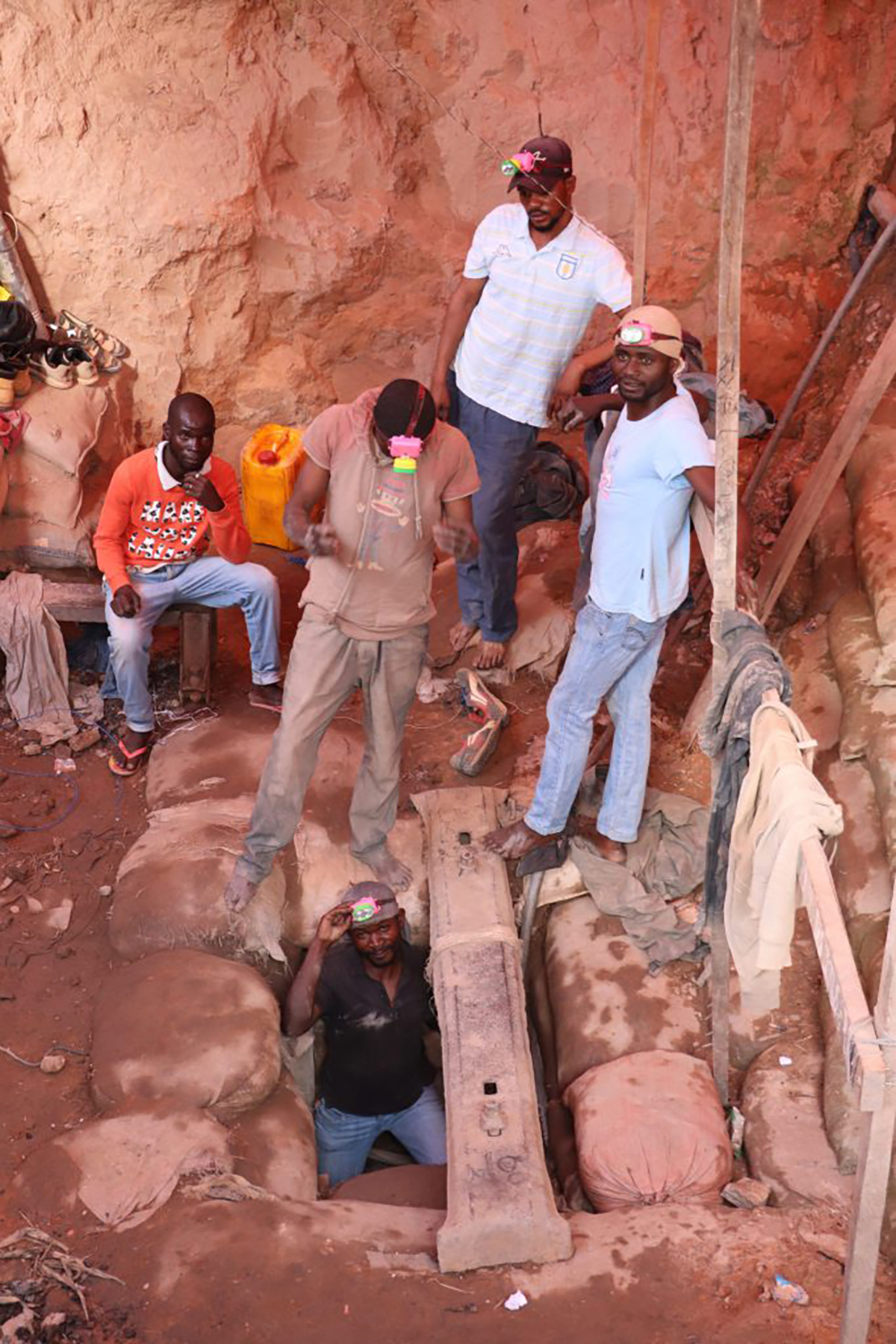

Professionalising the sector and making artisanal cobalt mining safe will also not be easy. The work is dangerous and harmful to health, and conditions are impacted by wider conflicts. Lasting impact will mean addressing underlying root causes, such as widespread poverty and a lack of support. That is why investment, as well as merely collaboration, is necessary. Funding can be channelled – in partnership with local actors – towards training, investment in structural improvements and access to schooling, to name just a few.

We also hope that the ASM Cobalt Framework which the FCA has co-developed, together with the RCI and RMI, will provide a progressive and practical structure for these improvements which for all actors to refer to, ensuring everyone is working towards the same goals.

Source: David Sturmes, Fair Cobalt Alliance

Supply chain actors must not fear complexity

As we have seen, the process by which cobalt goes from the ground to its ultimate destination is highly complex. In the case of cobalt, between the artisanal or industrial miners who extract the metal and the consumer purchasing the car or phone, there are intermediaries such as traders, refineries, makers of battery components, battery manufacturers, carmakers, and electronics companies.

This complexity has led many to invest in improving traceability so that they can reassure stakeholders and consumers that there are no associations with ASM mining or child labour. However, prioritising this investment risks bypassing a vital opportunity: the chance to lift thousands out of poverty through work that supports the energy transition.

Instead of using the complexity of these supply chains as an excuse for inaction, actors at each stage must harness their influence. Through initiatives such as the Fair Cobalt Alliance, influence can be leveraged positively, uniting the supply chain to provide mining communities with a fair share of the profits from the global energy transition, providing a dignified, safer and fairer living. Just as with the challenge of tackling climate change, there’s no time to lose.